CW: war, corpses, cannibalism, intrusive thoughts, blood, religious extremism

“This machine kills JayBay-stans--” etched onto the side of an air-to-surface missile. Log onto the live feed, right above the handbag ads. Stats? Eight-hundred-thousand dollars. Produced in the backwaters of some former swamp. Out of the congealed blood ‘n mud, family trees sucked on by mosquitos, and one-thousand-four-hundred pounds of subsonic might. Faster than any rushing river. It tumbles down, leaking beneath the hatches. Watch as the frightening mega-size of the bending Earth collapses into claustrophobic darkness... perfect hit, beautiful delivery. W’s in chat. Hearts galore. Beating red. “JayBay-stans when they stay silent about the allegations...” it disappears, gone all’uh sudden. Buried by perfect cheekbones, glittering in the sun of somewhere exotic enough.

Ah.

Natalia shakes her, stirring her awake from a deep, buzzing sleep. “Ah,” Yelena feels her heart drop. Natalia’s face frightened her, its lit side cratered and dark like a moon. They’d driven through the night, and parked underneath the cover of low trees. Yelena squeezed her face, her arms-- she’d hoped it was a dream, a hallucination. Fear and disappointed burned in her throat for a few moments, but it died away soon enough. “I’m thirsty... pitj,” she pointed at her mouth. Natalia stared blankly for a few moments, then reached down for a motor oil canister filled with water. Yelena drank from the greasy vessel with pained gulps, her throat heaving then shrinking, to Natalia’s simultaneous disgust and interest. She’d seen so many dead, littered along the sides of the road, that the strange animate movements of a living body seemed novel. She insisted, pulling the canister from Yelena’s hands, on pouring some of the clean water onto the Earth. She imagined humans growing from the soil like apples.

Natalia opened the door of the truck, seeking an escape from the dull stench of the truck, and parted the leaves to step onto the road. Slivers of orange fire came through the trees, casting embers before her feet. A stream had broken free from punctured pipes, and she washed her blackened feet in the icy water. She thought of its source, the rushing water that corrodes the reflection of all that comes across. She closed her eyes-- her face rushed beyond the splintered trees, pulp-y gore strewn over the floor and the now still branches. There comes the chill; rapacious, all her senses taken from her. She looked at her reflection, broken and otherworldly. The chill turned to a sharp flame that welled up into her heart. You won’t take me-- she slapped herself, and enjoyed the quieting pain as the flame petered out to a brittle warmth. She spied a few mushrooms at the side of the road, and pulled them out of the chalky soil. Yelena stretched her limbs, a few yoga poses, whatever she could remember. She smelled her clothes, heavy with her own stench. Natalia looked so small, shrunken; Natalia seemed to Yelena like a broken puppet as she stepped down the road beside the rusted guard rails with a cluster of mushrooms in her arms. Natalia dropped them on the asphalt, then poured some of the canister’s water to wash them of their mud. She offered them to Yelena, a shiny white mushroom in her palm: “jadovityj,” Yelena cried. Natalia shook her hand, shook her hand again, then ate it herself, a small smile escaping her mouth as she crunched and munched. Yelena waited, anxiously chewing her finger, then reached down to taste the mushrooms for herself. They were earthy and chewy; they tasted like the essence of the forest itself, sullen with decaying corpses and ancient decay. Tears welled up in her face-- the organic matter was a terrible reminder that she herself was still alive.

The truck took a few attempts to start, and Yelena worried that the fuel was draining rapidly from the tank. Natalia could not, or would not, speak of how many more miles laid ahead of them. Maybe she’d misunderstood Natalia’s childish symbols, and maybe Nay-toe had abandoned Yelena to her fate. While her eyes traced the sickening lines painted onto the asphalt, she thought of the many ways she might die. She thought of her own hunger, feasting on Natalia’s bones, drinking her blood. She thought of her skull flattened, pinkish goo spurting forth from her cavities, and Natalia’s dead face getting redder with her every swing into Yelena’s head. She wiped the sweat from her face, she knew these were childish fantasies, a petulant seeking of release. Natalia sucked on her thumb, watching the many burnt tanks, cars drenched in ash. They seemed like clay statues, brilliantly bleached by the lazy haze of morning sun. She tried to think of happier things-- a doe deer hobbled down ‘tween the stones, licking at a rotting tree branch. Where do they go when they disappear? They burrow their heads in little kingdoms of soil, far away from the whizzing of jet-powered bombs and howitzer shells. The hungry little rat has no mind for the rotting dead, their texture no different from the soft mushy branches or the hot mud. The bird sits perched upon the trees, distant and fearless, finding her safety in the emptiness of blue skies. The bunny cowers beneath the canopy. Run, little bunny, run; it will find you.

Those beautiful green eyes, staring back at you. She remembers it, scowling as it cowered in the tattered grass ‘tween the broken wooden fence. Its muzzle was sticky with old blood, its teeth tired and grey. It exposed its teeth, drawing in a wheezy breath. Natalia approached it, feeling her head thump as she extended a hand to it. She stared back, deeper into its eyes to lose herself in a sea of deep jade. Its grimace died away, raising its head as a whine escaped from its mouth. Now he seemed so small, in Natalia’s grasp, his fur like a tooth brush. The creature crouched, made a loud whine, then tore Natalia’s hand with his broken teeth. Blood seeped from the tear, oozing from her thumb to her index finger.

The camp laid in the canyon, surrounded by tall fences girded with rusting barbed wire and tattered flags. The rust embraced the metal with orange vines, a thread that ran from abandoned cars to shattered helmets and broken armaments. Yelena followed the symbols of stars, Nay-toe’s great crest, drawn in the sand. They left the truck beneath a few trees, beside other rusted cars covered in plastic bags and soggy cardboard. The towers overlooking the camp had fallen into disrepair, metal screws and loose steel plundered. Nay-toe’s presence was felt, not through her soldiers, but by the tents protected by her holy seal. They walked down a path, parted before them in a sea of tents. A few old men sat around a grill, their bellies fattened by cheap beer. Women washed their children, soapy water pouring down to a brown lake of open waste. Discarded plastic cracked beneath their feet like seashells as they passed by the tents, falling under the sharp gaze of the folk. Natalia pointed at them, then at herself; Yelena’s nervous trembling was broken by Natalia’s hand sudden grasping her own. An expression of kinship, but to protect whom? She saw men hanging from a pillar, their faces sunken and bulbous. Nay-toe’s light no longer reached us, for we’ve fallen into dark depths. They followed the chatter, the shouting, some words familiar; “bazar?” Yelena asked Natalia. Natalia’s face remained trained before her, her eyes watching the shadows between the tents.

The path opened up to bustling crowds, milling about many stands which sold plastic household goods, flags, souvenirs, knives, carvings, shoes... the stand beside them was covered in a blue tarp, with the uniforms of sports-teams hanging from plastic fasteners. The man, his beard black and thick like moss, waved and beckoned Yelena: “privjet, privjet-- lutsheij tseny.” Dozens of sneakers were arranged like a bouquet before him, in pink, red, blue. Beyond him a man played on a wooden flute, laid before him were medals full of stars and wings. Yelena inspects them, tarnished and misshapen. Natalia played with a few colorful pebbles, arranged by value across a large table. The woman at the table huffed when Natalia let them clatter onto the table. Some of the medals featured tanks, some featured corn and hemp. The world before her was a world of only commerce; without community, without commonalities like flags or words. The only thing that connected us was an exchange. And she’d remembered the symbols from her childhood, the shapes of the many languages and mannerisms that once mingled freely ‘tween the car parts and boutique military uniforms. Now it’s only memories of glints in another’s greedy eye, the dust that collects on a weary mind-- those of us left behind by the world have only the refuse of its yesterdays to hold and sell. Nay-toe takes, Nay-toe gives. Natalia’s thoughts slowly drifted away, and she felt herself overwhelmed by the smell of burning meat upon coals. Her stomach rumbles as she watched the meat turn on a spit, a man with an ashy face flapping a piece of cloth over it. Steady, she mumbles... she takes one and runs into the crowd, hearing the commotion behind her slowly recede away. She takes a turn into a dark, blue corner; sitting underneath the canopy of drying carpets, she gnaws on the meat.

Yelena drifted from one assortment of filthy plastic goods to another, her face warm as she studied the ways a CD tray, a broken bumper, foamy noodle-cups could be repurposed. She let herself be seduced into romance; to live off the plastic of the land, in harmony with garbage. She saw on the hill mansions of styrofoam, cardboard, gates made of molten figurines. She thought of pastoral nomads, roaming the black rivers of plastic, from one landfill to the next, fattening their horses on paper and battery acid. A slow death is what it means to be autonomous. This is how she overcomes her anxiety-- thinking of herself as an abstraction, a vector with a direction and nothing else. She is merely the effect of some great ancient cause, a sharp point shot by a cosmic bow. Have no fear; you’re merely an expression of Nay-toe’s will. She walks by a table arranged with broken electronic wares; phones with cracked screens, laptops missing keys, umbilical machines and octopus devices. Across a path of trampled fruit, she finds a tent surrounded by towers of books. They were in languages she could not understand, in scripts of cracked noodles and spikes, shapes made of iconograms and dripping ink... she approached the shortest tower and drew a book from the top: “Fluency in Love Languages,” the corners wilted by moisture. A few books strewn by the entrance of the tent were written in Russian, degraded but by the drawings evidently childish. She drew one at random, “cvetik semicvetk,” and entered the tent.

A bearded man sat on a carpet with his legs beneath him, a cigar burning in his mouth as he raised his hands to the sky like an arrow. He mumbled to himself, his eyes shut but twitching. “Ayin’pes dvats, ayin’pes das.” The star-encrusted crest of Nay-toe hung around his neck. Yelena shuffled closer, holding the children’s book like a shield over her heart. She cleared her throat. The man’s eyes suddenly opened and he twitched in surprise. “Gheneres,” he spat. Yelena shrunk in embarrassment, suddenly shy as if catching him nude. “Ne panimayu,” she croaked. The bearded man studied Yelena closely: her dirty shoes, coarse and matted hair, tattered Adidas jacket, a softness to her accent that betrayed a constitution alienated by the Zone. He remembered one of Kali Hichi’s thoughts: “lead the ‘iskatyl’ on his way. When he finds his ‘vetsy’ in what he’s looking for, you will find yours in him.” The bearded man pointed to his own heart, drawing a star with his fingers. “Siela,” he whispered. Yelena pointed to herself, “Yelena.” The bearded man shook his head, the ash from his cigar falling onto his hairy legs. He draw the star again, pointed to the sky, then pointed to Yelena’s chest: “siela.” He smiled, satisfied. Yelena tried to hold her laughter by forcefully biting her tongue, and placed the children’s book onto the table before the bearded man. “Ya khotel by kupitj.” The bearded man chuckled, and took a book from a stack beside him. He placed it beside the children’s book, and its red plastic cover glowed brilliantly beneath the candle light. He tapped the red book with his finger. Yelena read the cover, embossed with the words “the Twenty-Four Thoughts.” Yelena looked up from the book, her nose irritated and swollen. “Shto eta?” The bearded man put his hands above him, pointing again at the sky like an arrow. “Kali Hichi,” he pronounced each syllable clearly. Yelena took the last of the cakes she’d hidden in her jacket and placed it onto the table, carefully pondering his empty reaction. “Spasiba,” she mumbled before taking both books and leaving the tent with her head slack and covert.

THE FIRST THOUGHT OF KALI HICHI:

« In the beginning, Nay-toe created the Zone. Nay-toe had seen the creations of other GODS, ‘borg,’ and disliked how each act further and further infringed upon the infinite freedoms of nothingness. So when Nay-toe created the Zone, he created not things but possibilities, so that the Zone may hold in its nothings every desire, inclination, tendency, and want imaginable. And within the garden of this nothingness, MAN, or ‘monzhj,’ was finally free to live as he wanted. And-- ... »

Yelena shut the red book, feeling disorientated and alone. She looked at the sunken faces around her, penetrating her with their covetous gazes, hoping to attract a costumer. A stone sunk in her stomach, and she felt the contents well up into her mouth. She held the red book to her chest, shut her eyes, and prayed for the spell to last just a little longer. There is no life left for her to lose. Christine had taken it away from her.

She drifted down corridors, unsure of where she’d wanted to be... besides somewhere not where she was. The thought that she could not walk away from herself made her esophagus well up in pain. Her blurry vision became filled with lingerie, fat-masking underwear, bras hanging from hooks like a butcher. Thousands of football jerseys formed solid borders of colors and numbers, and she felt herself collapsed between rows of handbags so large they extended into the horizon. She felt vomit trickle from ‘tween her teeth. A few children laughed at her from broken windows above the stores. She opened the book again, reading on from where she’d stopped before.

« ... for a while, it was good. But the Zone was ancient, stretching from the beginning of time ‘till its theoretical end. And ‘monzhj’s’ time was not endless, but far more limited than his desires would allow. So ‘monzhj,’ needing to speak for the first time, said to Nay-toe: “Nay-tschoe! You need not know of death, for you are the maker of life. But I will die, and thus disappear, and with me disappear all desires, inclinations, tendencies, and wants. Then, what does that all amount to in the end?”

Nay-toe did not respond. Nay-toe never did respond.

And thereby, ‘monzhj’ become enlightened, and he understood: Nay-toe takes, Nay-toe gives. Eh, nothing you can do about that. »

Strange.

Natalia woke up from her sleep, feeling the sun pour through a hole onto her face. She saw a few children poke at a dead dog with a stick, their faces in curious glee as its eye oozed with purple blood. The children ran when Natalia approached, as if she were not a child anymore. Had it been longer than she’d thought? She looked at herself in a puddle of water beside a rusting pipe, and felt a crushing fear burn into her face. Her molten cheek, heavy with a lip of skin, startled her. She felt her body stiffen with tension as she tried to suppress the memory, fragments of red and orange accompanied by machine noises. She took the stick and drove it into the dead dog’s head, hearing it crack as she broke through its face. All better now. She felt thirsty, and set out looking for Yelena.

Oh. You might find yourself drifting from one stall to another, inhaling yet another whiff of old leather and indistinct spices. Down there in Butcher’s Lane, as the locals call it, every manner of vice the Zone might offer lies temptingly before you on sale. Or at least, that’s what the old wives say. You can see them whispering to each other, each arm carrying white plastic baggage filled with oranges, tobacco, used clothing, toiletries. Their heads are shielded from the sun by beautifully-etched patterned cloth, and their lips parched but still eager red. Further down the market, pass by the chain-link fences enclosing another ad hoc set of favelas, you can find men playing cards underneath the shade of mulberry trees overlooking a sandy football field. Did they leave their sleepy little villages, abandon their sheep and pigs, for the vast emptiness of possibilities within the Zone? Or did the Zone come for them first, slowly sucking up their periphery with ambient demand that hummed in the air like radiation? Suddenly the air sits uncomfortably in your belly, weighing down on every exhale. It’s here. You feel him now. Nay-toe’s heavy presence. The sand of your life slips through your fingers and becomes the glass panes of a luminous mall, overlooking the parking lot that spreads like blight over the valley. And no-one will listen to you talk about how the Zone once howled not with trucks but only dreams.

Oh. Yelena finds herself in front of a dazzling wall of t-shirts, all of them adorned with mythological figures; some contemporary, some forgotten. Ducks, dusty-haired heroes and heroines, and friendly monsters. Did the world arrive here late, or never at all? A child wore a superhero t-shirt, a little too large with its hem draped over his knees. He dug it up out of burnt wreckage, wore it like the tattered relic of an ancient and forgotten civilization. That shit boosie. She saw a figment of Christine beside her, a ghostly outline of her. She hung one of the shirts before herself, Raeggae Martin emblazed & embossed, with fat doob smokin’, wisps rising to the sky. She heard her voice; not words, but a rising lilt carved into the air... like if torn cloth could speak, a scissor down its throat. “Fuckin’ gay;” Christine spat. Yelena pulled out t-shirts with her hand, each one a new atrocity with garish colors and decals that crumble with touch. Out of the cracks of the bakery came Christine again, dressed in Balanciaga & Gucci, their threads frayed and leather dull: “being the kind of retard that wears fake co-tour.” From the sewers, she walked on by wearing basketball swag with the ‘GENUINE’ tag swaying like jewellery, Yeezyies caked with horse-archer dust. An army of her; they pull on my muddy rags, giggling at every frayed edge. “Wouldn’t you be embarrassed if they found you dead in this?” Yelena thought of how she’d look as a corpse, if her hair would be scattered like sunbeams and if her face would be pink and blushing. The emptiness of that thought made everything else feel hollow & artificial, as if the beautiful mountains there in the distance behind the river was merely a painting on a large wooden frame, turned to ochre pulp within the blink of an R-36’s detonation. Nothing remains but you and I, smoldering upon an orange disk. Let a flood of light wash out the rest.

Beside two t-shirts, on the left “Show Me Your Tits,” on the right “John 3:16,” Yelena saw in XXL a blown-up face-- his chin scruffy, sideburns long and unkempt, an expression of solid strength betrayed by sensitive eyes. Rendered only in black and white, a checkered scarf around his sleek neck. It can’t be. He’d disappeared. Forgotten as a suicide case. There were others. Behind the wooden bars. In M, L. Elon Rao’s face on all of them. She caught the shop-keep’s gaze, and pointed at the shirts everywhere. “Kto eta takoi? Etot chuvak.” The shop-keep smiled. He explained that he was a legend to the Muslims who once lived in the Zone, respected as a warrior who believed in an allegiance to all men despite his national origin. He said Elon’s grave had become a landmark in the Zone, guarded and protected by heavily armed nomads hardened by Nay-toe’s trials. He’s said to have lost his life in the final violent confrontation between the Christians and the Muslims, which resulted in the latter’s transfer and permanent exclusion from the Zone. The Muslims had lost their faith in Nay-toe, who had stood by and done nothing as the Christian forces went from home to home searching for young men to kill and young women to abduct. The shop-keep showed the long scar encircling his head. He explained that within this camp, a communal decision to respect all religions is enforced through threat of expulsion. The needs of commerce, he admitted, were not matters of GOD. He himself travels often from Turkey, paying off cargo ships to traffic goods through the Black Sea into the Zone. His Russian was perfect, fluid and rhythmically pleasing which made Yelena feel like a shoddy knock-off besides genuine Nike. While Yelena imagined piercing the skies above her like a burning rocket, Elon Rao had already lived & died for twenty lifetimes. Now he knew the other side-- gotta be so good that he never returned. She reckons, a few decades of boredom is a small price to pay for paradise.

And the first thought went on:

« Boredom thus became the disease which plagued only ‘monzhj,’ and none other of Nay-toe’s creatures... but this was no divine punishment. It was a mundane and earthly one. So to distract himself from boredom, ‘monzhj’ begun to tell himself lies about his desires, inclinations, tendencies, and wants. And thus, love between the first ‘monzhj’ and the first ‘zenzhj’ was born. And they together became the first ‘druzhina,’ or those who do Nay-toe’s will without even realizing it. So far, so good. »

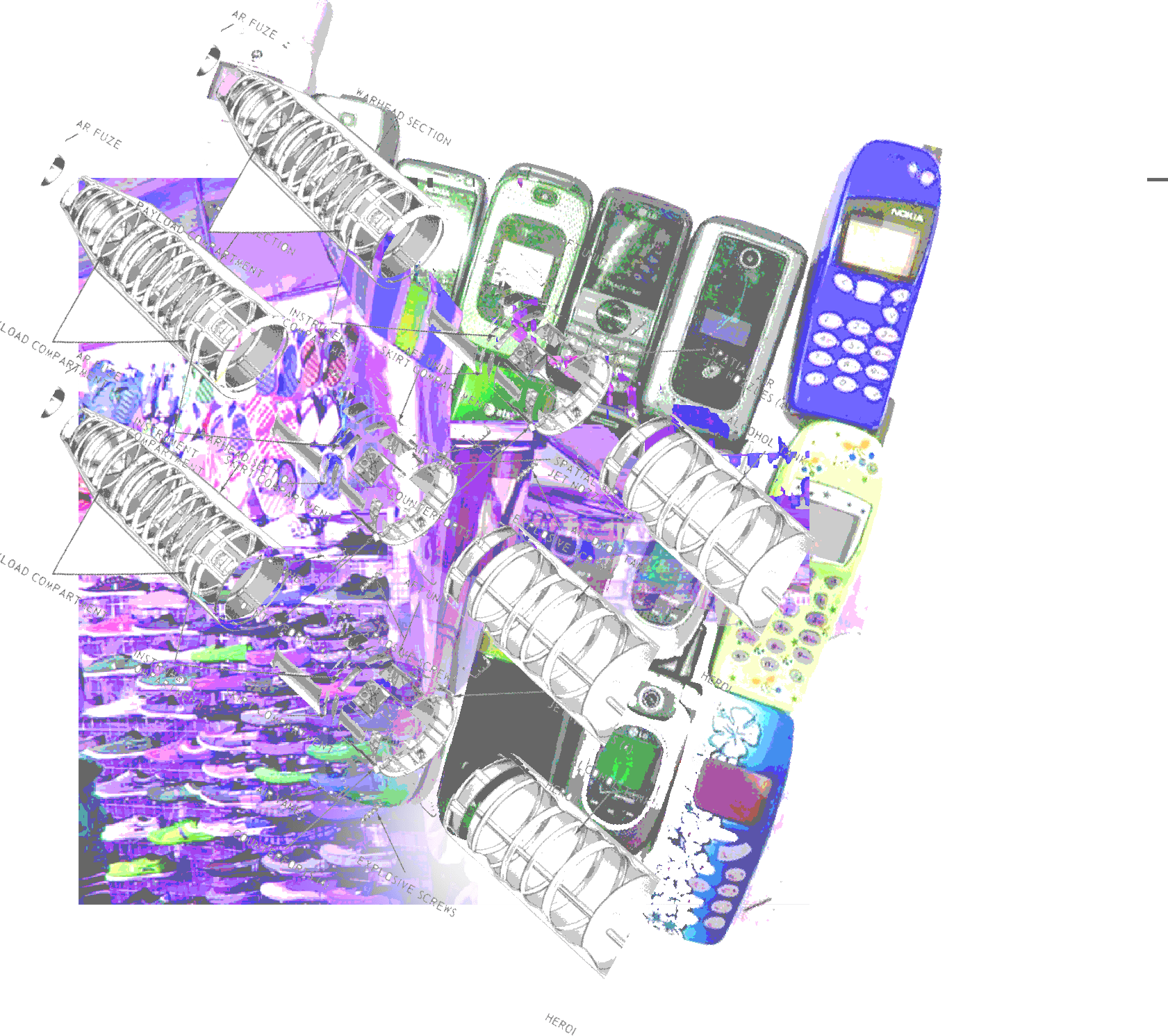

Yelena found Natalia overlooking several carpets adorned with phones: from little ancien régime Nokias to Galápagos clam shells, littered amongst fractured smartphones and forgotten portables. Hanging from a few fish hooks were phones abuzz with monophonic ring-tones, falling in concert together like a forest with birds, filling the air with shrill chirps and trills; these were the chimes of the Zone, catching Nay-toe’s stark winds and the last of the MIDI howls before that old world crumbles into disrepair. Yelena crouched down to look at a smartphone with a peculiar crack in the bottom of its screen; she’d remembered it had fallen from its perch onto the floor, while Christine posed with her freshly-oiled gun. Christine yelled a few curse words as she reached for it, then threw the phone back onto the floor once more as a punishment. Yelena picked up the smartphone, turning it around to find a sticker saying “bitch-made,” another of a fried egg, and a few more from clubs around the world meant to obscure the camera. From the bottom, there hung a jagged plastic fragment of the green-haired ‘n horned anime girl now missing her lower body. Yelena turned the phone around again, twice more; she yelped with recognition, relief, as if her entire life had regained its sharp purpose and function... a dull and rusty knife taken from its drawer and sharpened once more. She held down the square button but nothing awoke, the phone remained stoic and dark.

Natalia watched Yelena nervously chew her fingers as she studied the phone. A vulnerable chill washed over her; is this what this stupid foreigner was here for? Blood will spill from the wells merely for this little box of broken glass and plastic-- ah, but how could Yelena explain it? How could she say that Natalia is merely blind, that she sees only the world before her... and not the thousands which laid beyond the screen, melting into the infinite horizon. Yes; it’s surely there where Nay-toe lived... in that world of infinite desires and emptiness, of which this phone was merely a sacrament, a tool permitting a higher order of experience and consciousness. How could I explain it to you? The borders and meanings of flesh and blood melt away in the flood, and the boundaries of Ego overlap with its desires. Sell away that island of self ‘cuz only the formless, shapeless, may survive nothingness. How could I explain it to you? You, for whom the demands of the physical and the death it invites are your only guiding star.

Yelena offered the man behind the carpet her keys to the truck, begging him to take it. Natalia shook Yelena’s arm in protest, her face sullen as the claustrum of these cardboard walls and its voices hung over her like vultures. To trade the freedom of the open road, the singular chance at even another hour of life, for a broken telephone seemed like madness to her. “The truck’s leaking! It’s not use to us. It’s no use to me. I need this. This is what I came for!” Yelena yelped, forgetting in her agitation that she could not be understood. Natalia formed a point with her fingers and stuck it into Yelena’s ribs. “Boljne!” she yelped. Yelena shoved Natalia, with enough force to send her tumbling down onto the dusty ground. All the protest fled from Natalia’s body, like wind escaping a balloon, and she felt her own arms and legs grow heavy and slack. Yelena howled with sudden concern, “poryadke?” She reached down to hold Natalia’s light body in her arms, and though she felt Natalia’s heart thump heavily and saw Natalia’s eyes shake with burdensome tears, a powerful panic started to drag on every pained breath. “Shto sluchilesj? Natalia?” She took Natalia in her arms and looked at the man behind the carpet, who’d jumped onto his feet and gestured wildly with fingers and points. “Klinika,” he yelled. “Klinika,” he pointed down the street. Natalia uttered pained babbles, pulling on Yelena’s shirt, unable to tell her that nothing at all was wrong. While Yelena ran down the street, shouting “klinika? Gde? Mnye nade v kliniku,” Natalia thought of every muscle in her body, trying to conjure up any resistance that would stiffen the fingers or steady the limbs-- and thereby face the tides of nervous lethargy, the restless tiredness. But what good was resistance? To put off the inevitable, just to see another loathsome morning sun rise from the still black of the night sky? To delay the rot? To greedily trade oneself and her everything for another day of tasteless food and song? No. This was her protest. Against protest. Only yebanaya mudachka would sit in a river, her arms facing the waves, and command them to stop.